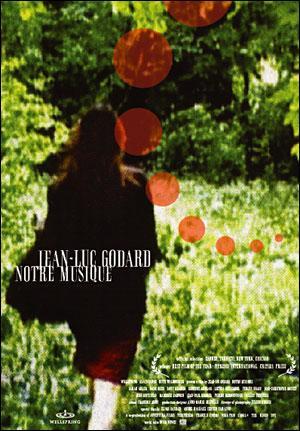

Our Music

- Original title

- Notre musique

- Year

- 2004

- Running time

- 79 min.

- Country

France

France- Director

- Screenwriter

- Cast

-

- Sarah Adler

- Nade Dieu

- Rony Kramer

Simon Eine

Simon Eine Juan Goytisolo

Juan Goytisolo Jean-Luc Godard

Jean-Luc Godard- Mahmous Darwis

- Jean-Paul Curnier

- Pierre Bergounioux

- Gilles Pequeux

Jean-Christophe Bouvet

Jean-Christophe Bouvet- Aline Schulmann

- See all credits

- Cinematography

- Producer

- Co-production France-Switzerland;

- Genre

- Drama

- Synopsis

- NOTE MUSIQUE (OUR MUSIC)

Shot and Reverse Shot

Imaginary: Certainty

Reality: Uncertainty

The Principle of Cinema:

Go Towards the Light and Shine it on Our Night

Our Music

Part poetry, part journalism, part philosophy, Jean-Luc Godard’s “Notre Musique” is a timeless meditation on war as seen through the prisms of cinema, text and image.

Largely set at a literary conference in Sarajevo, the film draws on the conflagration of the Bosnian war, but also draws on the Israeli/Palestinian conflict, the brutal treatment of Native Americans, and the legacy of the Nazis.

“Notre Musique” is structured into three Dantean Kingdoms: “Hell,” “Purgatory” and “Heaven.”

In the film, real-life literary figures (including Arab poet Mahmoud Darwish and Spanish writer Juan Goytisolo) intermingle with actors; and documentary meshes with fiction.

“Notre Musique” also follows the parallel stories of two Israeli Jewish women, Judith Lerner (Sarah Adler) and Olga Brodsky (Nade Dieu); one drawn to the light and one drawn towards darkness.

Through evocative language and images, Godard explores a series of conflicting forces:

death; life

dark, light;

good; bad

negative, positive;

real; imaginary;

activists; storytellers

vanquished; victor;

criminals; victims;

suicidal; hopeful

shot, reverse shot.

These opposing movements are eternal. They are the two faces of truth.

They are our music.

KINGDOM 1: HELL

Bright flashes of explosions set off images of war throughout the ages: gunfire, airplanes, tanks, battleships, executions, devastated countrysides, the holocaust and the atomic bomb. We hear a woman’s voice:

And so, in the age of fable

There appeared on earth

Men armed for extermination

Black and white intertwines with color. Some images are documentary footage; and some are taken from Hollywood movies like “Apocalypse Now,” “Zulu” and “Kiss Me Deadly.”

They’re horrible here.

With their obsession for cutting off heads

It’s amazing that anybody survives.

All the images are silent; the only sound we hear is the spare pulsing of a solitary piano: sometimes played very delicately; sometimes furiously hammered.

We consider death two ways:

The impossible of the possible And the possible of the impossible

KINGDOM 2: PURGATORY

Why Sarajevo? Because of Palestine and because I live in Tel Aviv I wanted to see a place where reconciliation was possible.

--Judith Lerner (Sarah Adler), “Notre Musique”

Jean-Luc Godard arrives in Sarajevo to give a lecture on “The Text and the Image” for the European Literary Encounters. He meets Ramos Garcia (Rony Kramer), who tells him about his life.

The Spanish novelist Juan Goytisolo gets in a car and is joined by an Israeli journalist, Judith Lerner (Sarah Adler).

Godard gets in another car with another Literary Encounters guest. Someone asks Godard why revolutions aren’t started by humane people. “That’s because humane people don’t start revolutions,” he says. “They start libraries.” “And cemetaries,” adds the guest.

Driving through the sites of the Bosnian war, Goytisolo says, “killing a man to defend an idea isn’t defending an idea. It’s killing a man.”

In another car, Literary Encounter guest C. Maillard (Jean-Christophe Bouvet) speaks passionately about the terrible impact of war. “Violence leaves a permanent scar,” he says. “To see your fellow man turn on you leaves a feeling of deep-rooted horror.”

All the Literary Encounters people arrive for a reception at the mansion of French Ambassador Olivier Naville (Simon Eine). After arranging a meeting with his former classmate, French writer Pierre Bergounioux, the Ambassador asks if writers know what they’re talking about. “Of course not,” says the writer. He explains that people who act don’t have the ability to express themselves about what they do; and likewise people who tell stories don’t know what they’re talking about.

Judith Lerner tells Ambassador Naville that he gave shelter to a young man and his fiancée in Vichy France in 1943; her mother was born in his apartment. Judith now wants to interview him about Israel and the Palestinians from the point of view of his onetime resistance to the Nazis. She says she doesn’t want the diplomat—she wants the man himself. “Not a just conversation,” she says, “just a conversation.” Naville says that accepting her proposal might make it necessary for him to resign.

As he explores the ruins of the Sarajevo Public Library, Juan Goytisolo recites a poem about the revelation of the “better fate” of the dead, and how this helps people cross more peacefully into darkness. A Native American couple approaches and the man speaks about the destructive legacy of Columbus on his people. “Isn’t it about time for us to meet in the same age?” he asks. “Both of us strangers in the same land,” the woman continues, “meeting at the tip of an abyss.”

In the lobby of the Sarajevo Holiday Inn, Judith Lerner interviews the celebrated Arab poet Mahmoud Darwish. Darwish points out that the Trojan victims were only discussed through the literature of the conquering Greeks, like Homer. As a Palestinian, he is a poet of the vanquished.

Olga (Nade Dieu), a Jewish Israeli of Russian descent, rushes through the streets of Sarajevo to attend Godard’s lecture. The director talks about the way language divides things. “Try to imagine; try to see,” he says. “With the first you say ‘look at that’; with the second you say ‘close your eyes.’”

Godard calls the shot and the reverse shot the basics of film grammar. He shows parallel images of Cary Grant and Rosalind Russell from Howard Hawks’ “His Girl Friday,” and explains that the shots are the same because Hawks doesn’t see a difference between men and women. “It is worse with two things that are alike,” says Godard. “Truth has two faces.” He relates an anecdote about German scientist Werner Heisenberg and Danish physicist Niels Bohr and their visit to Elsinor Castle. Heisenberg thought that the castle was nothing special; Bohr countered, “when you say it’s Hamlet’s castle…then it’s special.”

A student asks, “Can the new digital cameras save the cinema?” Godard is silent.

Cinema is made with what is called negatives in every language.- Awards

-

2004: San Sebastián Film Festival: FIPRESCI Film of the Year2004: European Film Awards: 2 Nominations2004: Swiss Film Awards: Nominated for Best Film2004: National Society of Film Critics (NSFC): nominated to Best Foreign Language Film.2004: Grand Prix - FIPRESCI Award: Best Film of the Year.

- Movie Soulmates' ratings

-

Register so you can access movie recommendations tailored to your movie taste.

- Friends' ratings

-

Register so you can check out ratings by your friends, family members, and like-minded members of the FA community.

Is the synopsis/plot summary missing? Do you want to report a spoiler, error or omission? Please send us a message.

If you are not a registered user please send us an email to [email protected]All copyrighted material (movie posters, DVD covers, stills, trailers) and trademarks belong to their respective producers and/or distributors.

For US ratings information please visit: www.mpaa.org www.filmratings.com www.parentalguide.org

US

US  Canada

Canada  Mexico

Mexico  Spain

Spain  UK

UK  Ireland

Ireland  Australia

Australia  Argentina

Argentina  Chile

Chile  Colombia

Colombia  Uruguay

Uruguay  Paraguay

Paraguay  Peru

Peru  Ecuador

Ecuador  Venezuela

Venezuela  Costa Rica

Costa Rica  Honduras

Honduras  Guatemala

Guatemala  Bolivia

Bolivia  Dominican Rep.

Dominican Rep.